Photo Corners headlinesarchivemikepasini.com

![]()

A S C R A P B O O K O F S O L U T I O N S F O R T H E P H O T O G R A P H E R

![]()

Reviews of photography products that enhance the enjoyment of taking pictures. Published frequently but irregularly.

Nadar's Lesson On Photography

30 October 2013

The Italian poet Guido Gozzano, admiring the difference between a goose and a man, summed it up succintly:

To be cooked is not sad

What's sad is the thought of being cooked.So the goose goes happily along, ignorant of its fate. And we bemoan our birthdays, one candle closer to the end.

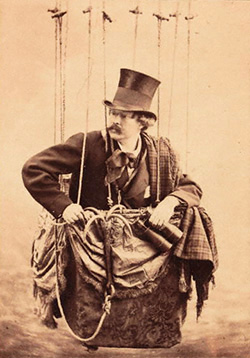

Nadar. In the gondola of a balloon, binoculars in hand, in 1863.

You expect a book reviewer to read the whole book before evaluating it. Even if it starts out well, a lot can go wrong in just a few words. And even if starts poorly, there can be method to the madness.

And while that's true of the photography books we formally review in the Book Bag, we're diverging a bit today to discuss Levels of Life by Julian Barnes. We've only read the first of its three essays, "The Sin of Height," but it's the one about photography.

Barnes explains that Félix Tournachon, the French photographer of the 1800s who came to be known as Nadar, put two things together that had not been put together before. Photography and Aeronautics.

Nadar got it into his head to take his Dallmeyer camera with a horzontal shutter he had patented along with him in the gondola of his balloon to photograph the French countryside.

It wasn't easy. The first shots were mysteriously blank. It turned out hydrosulfuric gas from the balloon had been ruining his silver baths. But it took a while to figure out what was going on. And the solution wasn't simple. He had to shut off the gas value, risking explosion, to get the shot.

As compelling as Nadar's aeronautic adventure is, Barnes doesn't skimp on the photographic adventure Nadar embarked upon.

He said that the theory of photography could be learnt in an hour, and its techniques in a day; but what couldn't be taught were a sense of light, a grasp of the moral intelligence of the sitter, and "the psychological side of photography -- the word doesn't seem to be too ambitious to me."

"His portraits surpass those of his contemporaries," Barnes writes, "because they go deeper." And he went deeper by chatting with his sitters, putting them at ease as he set up his "lamps, screens, veils, mirrors and reflectors."

You can see a few of those portraits in the Getty Museum's online gallery.

Nadar patented aerial photography in 1858, thinking it would revolutionize land surveying and military reconnaissance. But like a lot of great ideas, it didn't bring him the wealth and fame it might have. One of the saddest lines in the chapter is when Barnes describes the elderly Nadar sending a congratulatory telegram to Louis Blériot when he flew the Channel. The torch, one senses, had long been passed.

But it isn't the saddest.

Nadar's 55 year marriage to Ernestine, the 18 year-old girl he had wed in 1854 ended with her death in 1909. He had attended to her after her stroke in 1887. She would be lying down, her hair white, in a sky-blue dressing gown, with Nadar at her side, tucking her in, stroking her forehead.

Barnes writes, "Her dressing gown is bleu de ciel, the colour of the sky in which they no longer flew."

We put book the book down a moment to collect ourselves.

Barnes doesn't leave the chapter without mentioning the ultimate aerial photograph. A century after Nadar's only surviving aerostatic photos were taken, Apollo 8 took off for the moon. With a Hasselblad, William Anders took the first photo of an Earthrise, the Earth rising in the night sky of the moon. Anders said of it:

I think it struck everybody that here we'd come 240,000 miles to see the Moon and it was the Earth that was really worth looking at.

The "psychological side" of photography always appreciates the sitter's fear of "being cooked," as Gozzano put it, dressing them perhaps in a color of the sky. But the lesson, hard won by Nadar and perhaps why we find it in Barnes' book, is that photography can provide a perspective we would otherwise not appreciate until we had lost it.