Photo Corners headlinesarchivemikepasini.com

![]()

A S C R A P B O O K O F S O L U T I O N S F O R T H E P H O T O G R A P H E R

![]()

Enhancing the enjoyment of taking pictures with news that matters, features that entertain and images that delight. Published frequently.

Fifty Years After

22 November 2013

It is as sunshiny a day this morning as it was in Dallas five decades ago. And we have spent the morning reading what people remember of that weekend, of that man, of that time.

We don't weary of their stories.

We too still see the round speaker grill of the public address system high on the wall of our classroom. And, in our case, the stricken nun below it, absorbing the news that the first Catholic president had just been assassinated.

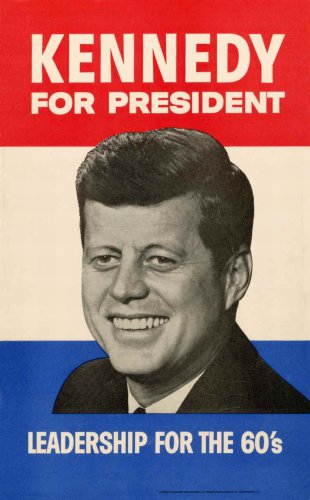

A New Generation. The poster that hung on the inside of our garage door.

How they had, those nuns, campaigned for him just a few years earlier, knowing only that he would do good.

We had run our own secret campaign. In the basement of our Henry Doelger home there was a huge campaign poster for Kennedy tacked onto the garage door. On the inside of the garage door. More like the picture of a saint than support for a candidate.

It was a red, white and blue poster. The image of JFK, smiling, was a simple black halftone. But it was enough.

I would come home from school and practice dribbling a basketball in the basement, my father having driven the car to work. Round and round I'd go, looking up at Jack Kennedy with a wink. You're going to do it, I would wink again for good luck.

What does a kid know?

℘

THE WORLD CHANGED in 1960.

In October the World Series went seven games, but you'd never know it from the public address system at school. The Yankees were playing the Pirates in Pittsburg while we were in class.

We'd learned by then how to snake an earpiece up our arm and rest our head in our hand to mask it so we could listen to the game on the transistor radio in our pocket. You could walk into any classroom that day and see at least six kids resting their head on their hand while looking attentively toward the teacher.

The occasional groan and eyes widened in delight would betray us but the nuns, too, wanted to know the score.

The Yankees had tied the series the day before. Convincingly. A 12-0 shellacking. And in the seventh game they would score nine more runs. Not for nothing were they the team of that era.

But Bill Mazeroski had the last word, hitting the game-winning homer in the ninth to take the series, the Pirates' first since 1925.

The next month, Senator Kennedy edged out Vice President Nixon for the presidency. To us it had seemed as inevitable as that home run.

℘

WE HAD LISTENED to Kennedy's speeches over and over again. We had used some of his funnier lines in our own campaign for student office. But mostly we had mined them for their thoughts.

We were a new generation, born in this century:

Let the word go forth from this time and place, to friend and foe alike, that the torch has been passed to a new generation of Americans, born in this century, tempered by war, disciplined by a hard and bitter peace, proud of our ancient heritage, and unwilling to witness or permit the slow undoing of those human rights to which this nation has always been committed, and to which we are committed today, at home and around the world!

We would not be compete with Sputnik. We would, instead, go to the moon:

If this capsule history of our progress teaches us anything, it is that man, in his quest for knowledge and progress, is determined and cannot be deterred. The exploration of space will go ahead, whether we join in it or not, and it is one of the great adventures of all time, and no nation which expects to be the leader of other nations can expect to stay behind in the race for space.

We would treat every American as we would wish to be treated, as we would wish our own children to be treated:

Today, we are committed to a worldwide struggle to promote and protect the rights of all who wish to be free. And when Americans are sent to Vietnam or West Berlin, we do not ask for whites only. It ought to be possible, therefore, for American students of any color to attend any public institution they select without having to be backed up by troops. It ought to to be possible for American consumers of any color to receive equal service in places of public accommodation, such as hotels and restaurants and theaters and retail stores, without being forced to resort to demonstrations in the street, and it ought to be possible for American citizens of any color to register and to vote in a free election without interference or fear of reprisal. It ought to to be possible, in short, for every American to enjoy the privileges of being American without regard to his race or his color. In short, every American ought to have the right to be treated as he would wish to be treated, as one would wish his children to be treated. But this is not the case.

We would, in short, ask what good we could do, not just for ourselves, but for the world.

Those speeches spoke to us as a child. And resonated with us as a young adult. And still, five decades later, nothing else quite stirs us the same way.

℘

IT'S EASY TO REMEMBER what we did that weekend five decades ago. We sat in front of the television.

We'd moved to a new house in 1960. Just built. There was room in the kitchen for a TV in the corner. A nice little black and white TV. We'd watch the news on it.

TV and radio were as immediate as news got then. You'd get the paper the next morning or afternoon, cementing events in your memory.

On the little black and white TV, we watched as Jack Ruby stepped in front of Lee Harvey Oswald. On the little black and white TV, we saw the casket of our President half a continent away. On the little black and white TV, we attended the funeral, watching the riderless horse march down Pennsylvania Ave. with everyone else who was there that day.

We were as solemn as a little kid could be when the world has changed.

℘

MY FATHER took us to the grave site at Arlington in 1964 on our way to see the World's Fair. With our little brother, we marched up the hill and proudly gazed at the eternal flame.

It was defiant. A flame that could be seen burning even in the bright summer sun.

Years later, as a freshman in Santa Barbara, and after a few more assassinations, we would stand at another eternal flame. Its three legs quote our slain leaders.

Martin Luther King, 1967:

The large house in which we live demands that we transform this worldwide neighborhood into a worldwide brotherhood. Together we must learn to live as brothers or together we will be forced to perish as fools.

Robert F. Kennedy, 1966:

I think that the motive that should guide all of us, that should guide all mankind, is to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of the world.

John F. Kennedy, 1963:

Let us take the first step. Let us, if we can, step back from the shadows of war and seek out the ways of peace. And if that journey is a thousand miles, or even more, let history record that we, in this land, at this time, took the first step.

We've run them in reverse chronological order here but the sequence ironically makes sense. JFK's exhortation to take the first step, uttered first, lingers longest.

℘

DONALD WILSON, the designer of the Kennedy poster that hung on the inside of our garage door, described the big question he had to answer about it:

The big problem in the summer of 1960 was whether to have a serious, mature poster or a smiling poster. At that particular time one of the major arguments being made by the Republicans was that he was not experienced enough to become president, and therefore, this led a lot of people around him -- and himself included -- in the beginning to think that he should have a rather serious mature poster. I convinced him that he looked wonderful smiling, but it wasn't easy....

So we have always remembered him smiling from the garage door. Radiating a confidence in the future despite the Cold War. Because he was confident in us. In what we could become. In what we might make of things.

He knew we were, like any kid, eager to take the first step.